An enhanced and colourised photograph of my Granny Jean Muriel Learmont Ross née Wynn on her wedding day.

Every family possesses a treasure trove of words of wisdom and knowledge passed down through the generations. My family is no different.

My late Granny, Jean Ross, was a fierce and wise woman who often reminded me that "we're a' Jock Tamson's bairns", a lowland Scots phrase that suggests that, beneath the surface, all people are fundamentally the same. Her forthright outlook on the world left an indelible mark on me from a young age.

Though the origins of this phrase are still debated, the sentiment it conveys is one that I have held close to me throughout my life. It serves as a reminder that, despite our differences, we are all part of the same human family, bound together by a shared humanity.

When I was younger I grew up knowing very little about half of my family and I never really felt comfortable talking about it. Truth be told, I didn’t bring it up with those close to me until I was 18 years old. At that point, I felt ready and I started to develop an appetite for knowledge about my origins and the people who came before me. It’s complicated, but if I were to put it into a few words, it’s like growing up having a feeling that part of your identity is missing, amongst other emotions.

From conversations I’ve had over the years with friends who have similar backgrounds, I’ve realised that this can be quite common. However, I know that some have no interest in learning any more, and are content with their lives and a sense of who they are. It’s a very personal choice and there is no right or wrong approach, it’s about what feels right for yourself.

Over the years my family research has taken many twists and turns, from discovering famous historical figures are ancestors, to making contact with a living sister that my Grandpa Edward Ross didn’t know about, to discovering via a DNA match that I had, unbeknown to me, recruited one of my cousins as a key member of the digital team at SNP HQ. More recently, I’ve connected with half of my family that I didn’t know. It’s been an emotional rollercoaster that is still ongoing, but one that I have enjoyed and found fulfilling.

I find ancestry research a bit like how I imagine some people find the problem-solving of a Crossword, Sudoku or Wordle. It’s detective work and problem-solving, you have to piece lots of pieces of historical data together to build the fullest picture possible of each individual and build the highest level of confidence in your conclusions. You can use a mix of generational stories, family records, newspaper archives, military records and DNA analysis to build the fullest possible picture.

When my Granny, who was formerly a Librarian at the National Records of Scotland estate, discovered I was curious about our family history, she asked me to find out more about her family lines. She knew she had family from Edinburgh, Dumfries and Dalbeattie, with some close relatives moving to Canada, but she also suspected that there were relatives from elsewhere.

And she was right.

When I trawled through the more recent family parish registry records, there was one that stood out to me; a marriage certificate for Christina (Christian) Gifford and James Hunter. On the ochre-coloured parchment and other connected records, aged by the passing of time, I could see that they had married in Leith in the 1860s, after migrating to the area from Shetland. Both of them came from farming and fishing backgrounds.

Marriage certificate for Christina Gifford and James Hunter (Leith, 1863).

In the 19th century, there was a growing Shetlander community in Leith, alongside Liverpool, New Zealand and the USA. Population pressures on Shetland, made worse by some being cleared from their lands in favour of sheep that were seen by the Lairds as more profitable, kickstarted several waves of migration.

Shetland viewed from space (Excluding the Fair Isle).

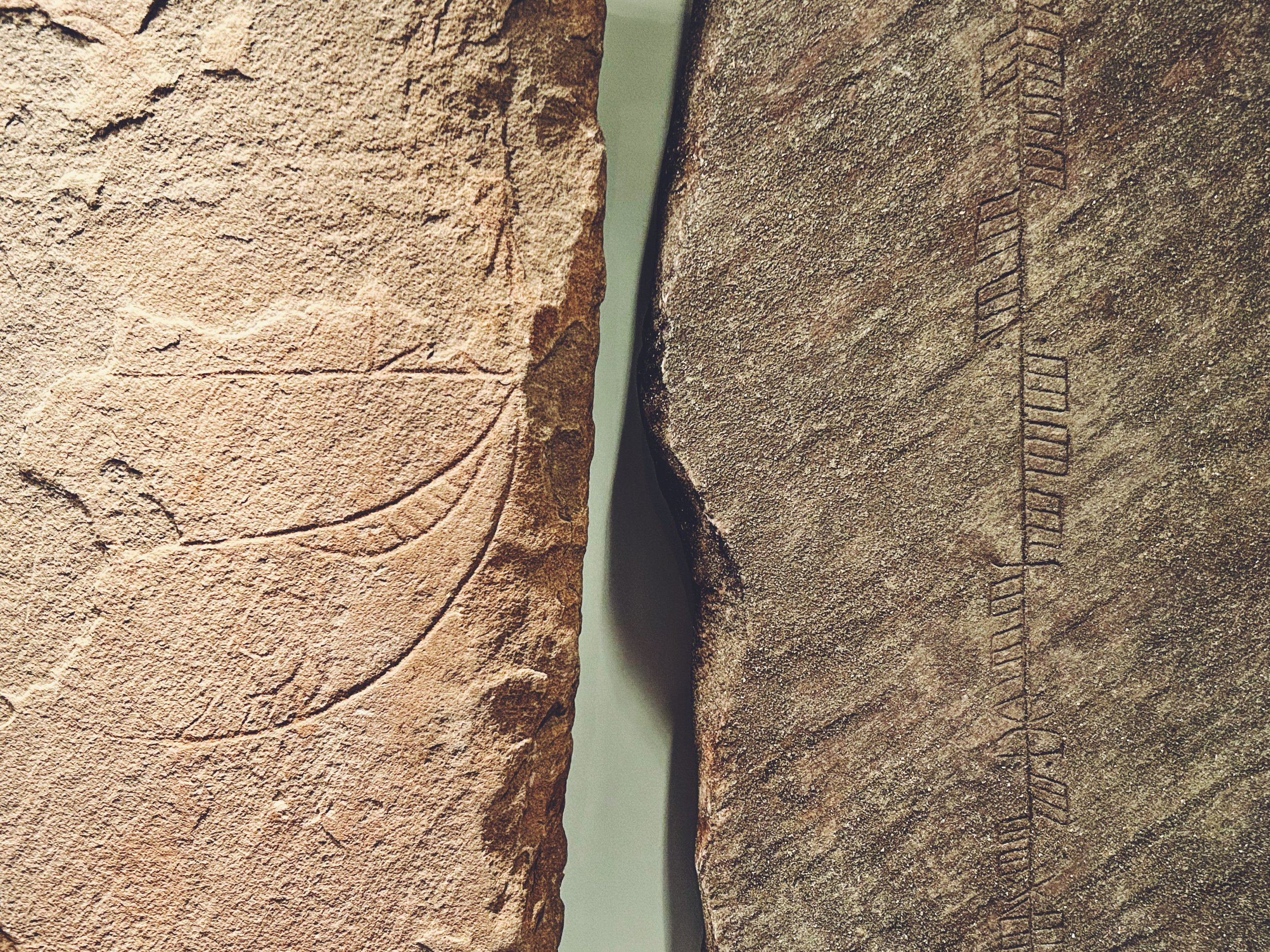

Shetland, an archipelago of around 100 islands in the North Sea, is home to a rich history dating back to the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Iron Age and Pictish periods. The island's capital, Lerwick, is closer to Norway than to Edinburgh, which is reflected in the strong influence of Viking settlers who arrived later in the 9th century and left their mark on the local language, culture, and way of life. The language they used evolved into the West Nordic language Norn, which survived in Shetland into the 19th century.

In 1472, Shetland became part of Scotland, and with that came an influx of Scottish landowners. However, many of these landowners were ruthless and unscrupulous, viewing Shetland as a means to make money at the expense of the islanders who had lived and worked the land for generations.

One aspect of island life that was affected by this change was crofting, a traditional system of land management that involved dividing the land into small sections and redistributing them among tenants to ensure equal access to both good and bad land. This system, known as runrig or rig-a-rendal, was viewed by some as outdated and ineffective.

The arrival of Hanseatic merchants in the 14th century brought economic prosperity to the island, as tenant farmers sold fish to these European traders. However, with their demise in the 17th century, the local lairds stepped in to fill the economic void, leading to an age of persecution for tenant farmers. The lairds adapted their estate business models and branched into the lucrative fish trade, buying fish from their tenants for a pittance and changing tenancy agreements to force tenants to fish and sell exclusively to them.

This shift in focus towards fishing led to a steep increase in the population of the islands between 1811 and 1861, as young couples were encouraged to marry and add new crofts to the land. However, this growth was unsustainable, as the land could not support the increasing population. As a result, 19th-century Shetland was marked by poverty and hunger, with the threat of starvation always looming.

View in Leith Docks, George Washington Wilson (1860).

During the Victorian era, Shetlanders who had migrated to the Leith area established a social association known as the "Leith Thule Club". Following World War I, and with continued migration from Shetland to the South, many Shetlanders arrived in Leith via the regular boat service, known as the "calling boat". In 1928, those living in the Edinburgh and Leith area re-formed the Association for their social benefit. In 1962, the Association acquired a property at 11 Pilrig Street in Leith, naming it Zetland Hall and using it as their central hub.

Christina and James were such migrants from Shetland to Leith. Christina left behind her parents Ogilvy Gifford and the late Mary Copland, who both lived at the Northerhouse (Norderhus) croft, nestled on the northeast coast of Bressay, looking out towards Noss and the icy blue waters of the North Sea. Together, Ogilvy and Mary had 12 children, with Ogilvy having a further 7 children with his second wife, also called Mary. All 19 children lived in Noss Sound 1, 2 and 3 crofts right next to each other. The family was a microcosm of the population pressures on the island. As you can imagine, this means that we have many relatives in present-day Bressay, Shetland, and lands further away.

Last week, I embarked on a journey to Shetland with my partner Triona to take in Up Helly Aa, a fire festival that marks the end of the Yule season, and to uncover more about its people, history, and culture. My Granny had wanted me to visit on her behalf, and I promised her that I would one day. I had visited Shetland before, but on both occasions, I was on the campaign trail and didn't have enough time to truly explore. However, upon closer examination of records and some further research, I realised that whilst recording a campaign film for the talented Tom Wills on the summit of the Ward of Bressay looking out towards Lerwick, if I had just turned around 160 degrees I would have been looking in the direction of the remains of my ancestors' croft, Northerhouse, amongst other connected buildings. The stoic dry-stone structure had been a part of the landscape there for over 160 years.

During my research, I came across a letterpress illustration of the croft created by the Victorian artist J.T. Reid for his book “Art Rambles in Shetland”, which was coincidentally created when my ancestor Ogilvy and Mary Goudie, his second wife, lived there. This gave me an idea of what the croft looked like when they lived there, and I discovered that it was known as the "Ferryman's cottage". This meant that alongside farming at the croft and fishing, Ogilvy ferried Shetland folk and visitors across from Bressay to Noss, which is now a nature reserve.

The Ferryman’s Cottage, Bressay, Shetland. Illustrated by J.T. Reid for his book Art Rambles in Shetland (1869).

During a conversation with a woman who is likely Mary Goudie, in his book J.T. Reid gives an account that the Gifford family was deeply proud of their Shetland heritage. Reid describes an encounter he had at Northerhouse, where he requested to hire a boat to travel from Bressay to Noss. However, Mary informed him that her husband, Ogilvy, was out fishing and proceeded to signal a shepherd who was repairing a boat on the opposite beach. She reassured Reid of the safety of the journey by vouching for the shepherd's capabilities as a true Shetlander, distinct from "thae Scotch bodies".

As my research delved deeper into the history of the Gifford and Copland families, I discovered that the Giffords, a Scoto-Norman family that originated in Normandy in France before 1066, was first recorded in Shetland in 1567 with the arrival of John Gifford, a church minister. He is said to have been the second son of John Gifford of Sheriffhall in Midlothian. The family then built the first building of Busta House in 1588, with further buildings added over the years, making it the oldest continuously inhabited home in Shetland. Meanwhile, according to a descendant of the Copland family on Shetland, they originated from a 17-year-old from Berwick upon Tweed, who survived a shipwreck on the VE Skerries and was rescued by Bessie Simpson, whom he later married.

Busta House, Brae, Shetland

Shetland's rich heritage is reflected in the surnames of my ancestors and the people who live there, which include both heritable family surnames passed down through generations and primary patronyms that use the father's first name and an affix denoting relationship, like Anderson. This is a result of the blending of Scottish and Scandinavian cultures and traditions that have occurred over the years.

Tracing the female line in my ancestry has been a journey that has taken me back as far as the earliest parish records available. Unfortunately, the earliest available only dates back to 1696, found in Tingwall. To delve deeper into our heritage, I turned to DNA testing.

Three main types of DNA tests can provide insight into your ancestry: autosomal, Y-DNA, and mtDNA. Autosomal DNA testing gives an overview of your ancestors from the past five generations. My test confirmed that I have Shetlander DNA and that I matched with descendants of Shetlanders in my family tree, which verified my findings from the parish records. Y-DNA testing, which only applies to males, traces the direct paternal line, while mtDNA testing, which applies to both males and females, traces the direct maternal line. These tests can provide a more comprehensive understanding of your heritage and help you to understand the long-term migration of your ancestors.

Ancestral DNA testing types diagram.

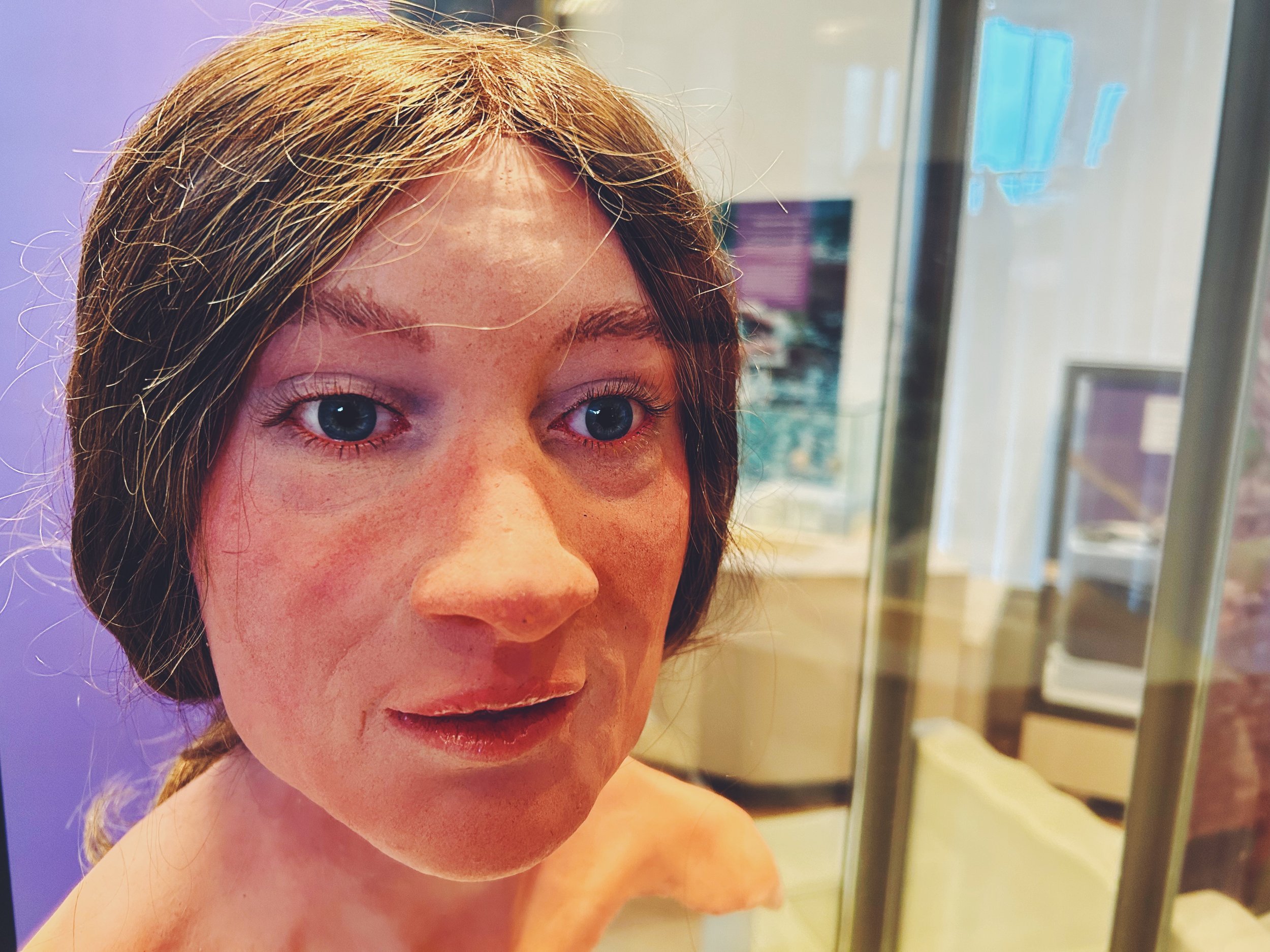

Tracing my family's ancestry using DNA testing has led me to an unexpected discovery. By testing for our mtDNA haplogroup, which traces our female lineage, I found that our haplogroup H13a1 is not commonly found in the population of modern Scotland and the UK. The results showed that our lineage can be traced back to a woman who possessed a unique genetic mutation that occurred around 12,000 years ago. This marker is most commonly found in the Caucasus Mountains region of Europe, specifically in present-day Dagestan and Georgia.

Present day mtDNA H13a1 haplogroup distribution map.

At some point in history, before the earliest Shetland parish record I have in the 1700s, a female descendent of a woman from this region migrated to Shetland, a distance of nearly 4,000 km as the crow flies.

Gamsutl, the location of an ancient mountain village in Dagestan.

While I cannot conclusively prove how this came to be with even a modest level of confidence without records, it is nonetheless fun to speculate.

The possibility of the first woman who possessed the mtDNA haplogroup coming to Shetland relatively recently rather than 12,000 years ago is supported by the lack of evidence of a significant number of descendants in Scotland sharing the same DNA marker, which would have likely occurred should there have been an earlier migration.

In the year 1040, according to the Georgian Chronicles, a Viking expedition led by Ingvar-the-Far Travelled is said to have visited the region. This visit is also described in Yngvars saga víðförla, which adds credibility to the account. It is possible that the Vikings captured a woman as a slave and brought her back to Scandinavia or the Kievan Rus on their ship in such an expedition. It is also possible that one of her female descendants ended up in Shetland, which was colonised by the Vikings, who later became Norse settlers.

Despite the possibility of this explanation, the true origins will likely never be fully known. The passage of time has resulted in the loss of many records, stories and historical accounts that could have helped to provide an answer.

As we consider the fact that 12,000 years have passed since the mutation of a specific haplogroup in the Caucasus Mountains region and its presence in Shetland, it is important to remember that countless individuals with their own unique lives, experiences, dreams, and loves have existed during that time. Many of their stories have also been lost.

I have described one section of my Granny Jean Ross’, and therefore my own, recorded ancestry spanning several generations. Every single person currently on this planet has a story like this, indeed, every person that has ever existed, right back to the first humans who migrated out of Africa and those before them. That’s your ancestors. It’s both incredible and humbling to think of it this way. You, and everyone you know, are one part of the rich tapestry of the story of human development that goes back over two million years.

When we learn about the history of human evolution, migration, and development, and discover more about our ancestry, we are reminded of the incredible diversity that exists among humanity. We come to understand that people often have more in common than we initially realise and that there is much more that unites us than divides us.

I can personally attest to this as I delved deeper into the history of my own family, tracing the origins of my Granny's lineage, starting from Leith, then to Shetland, and ending up in the Caucasus Mountains region in present-day Georgia and Dagestan.

And what will this soothmoother say to friends and family that I discovered about Shetland and my ancestry on my return to Edinburgh?

Today, Shetland is at the forefront of innovation, with industries like tourism, agriculture, aquaculture, fishing, oil and gas, renewable energy, space technology and the creative sector driving its economy.

That these islands, located 60 degrees north, are not only steeped in history and rich in culture, but they are also home to warm and generous people who live amidst breathtaking wild nature and stunning coastlines.

Well, and Vikings obviously.

Ross Colquhoun

A proud son of Shetland

Flaming torches being thrown into the Viking Galley at Up Helly Aa in Shetland.

I’d like to thank the Shetland Family History Society, specifically Jasmine Moncrieff in Lerwick, and Hazel Anderson, Robin Hunter and Theo Smith on Bressay, who have helped me with my family research and shared their incredible local knowledge. And Chris Dyer at Garths Croft who shared his invaluable archeological and historical knowledge with us. Those who we met during our time visiting the islands have left us with unforgettable warm memories that we will pass on to future generations.

Photographs of our trip to Shetland